Originally posted on World I Literature, Art, and Cinema.

Too often those who did not participate in the fighting of World War I tried to sanitize it, make it something grander than tens of millions groveling in the mud, piss, and shit of the trenches of the Western and Southern European fronts or forcing their way through the woods of the Eastern Front. Ideals such as “making the world safe for democracy” were often fed to the Doughboys, the raw American recruits who began arriving in France in late 1917 after the United States entered the war on the side of the Allies. The books and movies that follow often would juxtapose this naive idealism with the shell bursts and splattered limbs of blasted soldiers. But the front-line struggles often felt clichéd, something to be overcome on the way to victory than something that became an intrinsic part of a soldier’s life.

For African American soldiers, World War I took on a different face than that their white comrades saw. If this were indeed a war to spread democracy, then what about the endemic racism that they experienced each and every day? From the South’s segregation to the North and Midwest’s politer forms of discrimination, black enlistees into the American Expeditionary Force were reminded daily of the differences between being “free” and “equal”: substandard food; poorer housing,; lack of basic supplies for their units; segregated units; having to use broomsticks instead of actual guns – each of these added to the staggering number of abuses and insults that these soldiers faced even before they boarded (segregated, of course) ship for France.

Yet despite all of this, African American soldiers acquitted themselves admirably in World War I. One particular unit, the 369th Infantry Regiment, gained particular glory as they, fighting under French command, gained such a reputation that the Germans simply referred to them as “the Harlem Hellfighters.” They were the first Allied unit of any nation or color to reach the Rhine River, and while they received a parade in February 1919 upon their return home to New York, their legacy has faded somewhat, due to greater emphasis placed on the individual heroism of soldiers like Alvin C. York as well as the still-entrenched racism of the time.

Acclaimed graphic novelist Max Brooks (World War Z) in his latest graphic novel, The Harlem Hellfighters, brings to life the experiences of the New York 369th. Although many of the characters are fictionalized, several are based on historical figures who did serve in the US Army. When the April 1917 call for volunteers went out, men of all backgrounds and origins answered the call. Lawyers, ministers, bricklayers, recent immigrants from the Caribbean. Each of them were united only by the color (or shades of color) of their skin. They experienced hardships in camp and more when on leave during training in South Carolina. Brooks and the illustrator Caanan White show these trials in concise yet memorable detail:

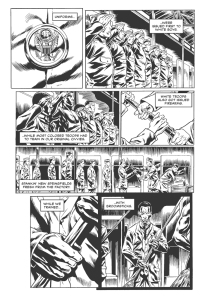

The

page image to the left is taken from p. 34. Here we see the 369th

lined up, but they have no uniforms; they are forced to train in their

civilian clothes. As the firearms are distributed to white soldiers,

broomsticks are passed out to the regiment. Even worse, the regiment

has been warned about how to comport themselves when they go on leave

from their training base in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Another

all-black unit recently got into a race riot in Texas and thirteen

soldiers were hung for mutiny as a result. Brooks and White tell this

story of racist abuse leading to murderous violence straightforwardly,

with the images of sneering Southerners inflaming the soldiers to

violence in order to make a point about the perilous position of African

American soldiers in 1917: are you damned any which way you do it, but

acting out makes you dead quicker.

The

page image to the left is taken from p. 34. Here we see the 369th

lined up, but they have no uniforms; they are forced to train in their

civilian clothes. As the firearms are distributed to white soldiers,

broomsticks are passed out to the regiment. Even worse, the regiment

has been warned about how to comport themselves when they go on leave

from their training base in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Another

all-black unit recently got into a race riot in Texas and thirteen

soldiers were hung for mutiny as a result. Brooks and White tell this

story of racist abuse leading to murderous violence straightforwardly,

with the images of sneering Southerners inflaming the soldiers to

violence in order to make a point about the perilous position of African

American soldiers in 1917: are you damned any which way you do it, but

acting out makes you dead quicker.

The story quickly shifts to the 369th’s departure for France and the ignoble tasks that await them there until they are transferred to French command. Brooks skimps on the details behind that transfer, making it seem that it might be part and parcel with the discriminatory actions taken against all-black units, but there are records that hint that this transfer might have been due more to manpower needs and less due to separating black and white American soldiers. This is one of a few occasions where Brooks simplifies the order of events in order to make his narrative stronger. This is not a condemnation of doing this, but rather a reminder that despite the heavy doses of historical fact and detail here, there is some necessary artistic license done in order to make the action hotter and heavier.

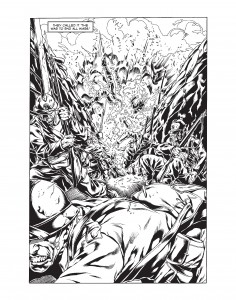

The

illustrations of the actual fighting convey well the confusion and

violence of trench warfare. The choice of illustrating everything in

black and white does, however, make it difficult to discern characters

from shell fire explosions, and there are times where the gore is

perhaps too well-illustrated, as images of blown-up bodies take on a

cartoonish quality on occasion. This is perhaps the worst criticism

that can be made of the illustrations, as for the most part, White’s

illustrations add a sense of gravitas to the story that Brooks is

telling.

The

illustrations of the actual fighting convey well the confusion and

violence of trench warfare. The choice of illustrating everything in

black and white does, however, make it difficult to discern characters

from shell fire explosions, and there are times where the gore is

perhaps too well-illustrated, as images of blown-up bodies take on a

cartoonish quality on occasion. This is perhaps the worst criticism

that can be made of the illustrations, as for the most part, White’s

illustrations add a sense of gravitas to the story that Brooks is

telling.

Brooks on the whole does an outstanding job of creating memorable characters, even if some of these appear only on a handful of pages. He shows their drive and determination in the midst of hatred and denial, but he does not reduce his characters, real and fictional alike, to mere archetypes. He shows how class and regional differences do affect viewpoints and while he does not directly state it, he does hint that some of these characters go on to play important roles in the 1920s and 1930s Harlem Renaissance. It is a powerful set of tales contained within the larger narrative of the 369th Infantry Regiment and it helps bolster the heroic qualities of “the Harlem Hellfighters.” The Harlem Hellfighters might be in places “too Hollywood” for the actual historical unit, with occasionally graphic scenes of death and fighting, but for the most part, it is a lovingly-rendered fictionalization of an oft-overshadowed World War I American unit and as such, it is worth reading as a testimony to the lives of those who fought even when others within the country would rather forget that they ever existed. One of the best historically-based graphic novels I have ever read.

Too often those who did not participate in the fighting of World War I tried to sanitize it, make it something grander than tens of millions groveling in the mud, piss, and shit of the trenches of the Western and Southern European fronts or forcing their way through the woods of the Eastern Front. Ideals such as “making the world safe for democracy” were often fed to the Doughboys, the raw American recruits who began arriving in France in late 1917 after the United States entered the war on the side of the Allies. The books and movies that follow often would juxtapose this naive idealism with the shell bursts and splattered limbs of blasted soldiers. But the front-line struggles often felt clichéd, something to be overcome on the way to victory than something that became an intrinsic part of a soldier’s life.

For African American soldiers, World War I took on a different face than that their white comrades saw. If this were indeed a war to spread democracy, then what about the endemic racism that they experienced each and every day? From the South’s segregation to the North and Midwest’s politer forms of discrimination, black enlistees into the American Expeditionary Force were reminded daily of the differences between being “free” and “equal”: substandard food; poorer housing,; lack of basic supplies for their units; segregated units; having to use broomsticks instead of actual guns – each of these added to the staggering number of abuses and insults that these soldiers faced even before they boarded (segregated, of course) ship for France.

Yet despite all of this, African American soldiers acquitted themselves admirably in World War I. One particular unit, the 369th Infantry Regiment, gained particular glory as they, fighting under French command, gained such a reputation that the Germans simply referred to them as “the Harlem Hellfighters.” They were the first Allied unit of any nation or color to reach the Rhine River, and while they received a parade in February 1919 upon their return home to New York, their legacy has faded somewhat, due to greater emphasis placed on the individual heroism of soldiers like Alvin C. York as well as the still-entrenched racism of the time.

Acclaimed graphic novelist Max Brooks (World War Z) in his latest graphic novel, The Harlem Hellfighters, brings to life the experiences of the New York 369th. Although many of the characters are fictionalized, several are based on historical figures who did serve in the US Army. When the April 1917 call for volunteers went out, men of all backgrounds and origins answered the call. Lawyers, ministers, bricklayers, recent immigrants from the Caribbean. Each of them were united only by the color (or shades of color) of their skin. They experienced hardships in camp and more when on leave during training in South Carolina. Brooks and the illustrator Caanan White show these trials in concise yet memorable detail:

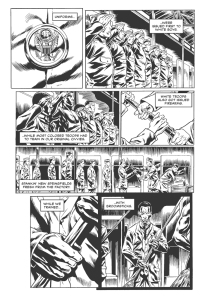

The

page image to the left is taken from p. 34. Here we see the 369th

lined up, but they have no uniforms; they are forced to train in their

civilian clothes. As the firearms are distributed to white soldiers,

broomsticks are passed out to the regiment. Even worse, the regiment

has been warned about how to comport themselves when they go on leave

from their training base in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Another

all-black unit recently got into a race riot in Texas and thirteen

soldiers were hung for mutiny as a result. Brooks and White tell this

story of racist abuse leading to murderous violence straightforwardly,

with the images of sneering Southerners inflaming the soldiers to

violence in order to make a point about the perilous position of African

American soldiers in 1917: are you damned any which way you do it, but

acting out makes you dead quicker.

The

page image to the left is taken from p. 34. Here we see the 369th

lined up, but they have no uniforms; they are forced to train in their

civilian clothes. As the firearms are distributed to white soldiers,

broomsticks are passed out to the regiment. Even worse, the regiment

has been warned about how to comport themselves when they go on leave

from their training base in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Another

all-black unit recently got into a race riot in Texas and thirteen

soldiers were hung for mutiny as a result. Brooks and White tell this

story of racist abuse leading to murderous violence straightforwardly,

with the images of sneering Southerners inflaming the soldiers to

violence in order to make a point about the perilous position of African

American soldiers in 1917: are you damned any which way you do it, but

acting out makes you dead quicker.The story quickly shifts to the 369th’s departure for France and the ignoble tasks that await them there until they are transferred to French command. Brooks skimps on the details behind that transfer, making it seem that it might be part and parcel with the discriminatory actions taken against all-black units, but there are records that hint that this transfer might have been due more to manpower needs and less due to separating black and white American soldiers. This is one of a few occasions where Brooks simplifies the order of events in order to make his narrative stronger. This is not a condemnation of doing this, but rather a reminder that despite the heavy doses of historical fact and detail here, there is some necessary artistic license done in order to make the action hotter and heavier.

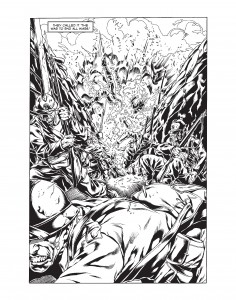

The

illustrations of the actual fighting convey well the confusion and

violence of trench warfare. The choice of illustrating everything in

black and white does, however, make it difficult to discern characters

from shell fire explosions, and there are times where the gore is

perhaps too well-illustrated, as images of blown-up bodies take on a

cartoonish quality on occasion. This is perhaps the worst criticism

that can be made of the illustrations, as for the most part, White’s

illustrations add a sense of gravitas to the story that Brooks is

telling.

The

illustrations of the actual fighting convey well the confusion and

violence of trench warfare. The choice of illustrating everything in

black and white does, however, make it difficult to discern characters

from shell fire explosions, and there are times where the gore is

perhaps too well-illustrated, as images of blown-up bodies take on a

cartoonish quality on occasion. This is perhaps the worst criticism

that can be made of the illustrations, as for the most part, White’s

illustrations add a sense of gravitas to the story that Brooks is

telling.Brooks on the whole does an outstanding job of creating memorable characters, even if some of these appear only on a handful of pages. He shows their drive and determination in the midst of hatred and denial, but he does not reduce his characters, real and fictional alike, to mere archetypes. He shows how class and regional differences do affect viewpoints and while he does not directly state it, he does hint that some of these characters go on to play important roles in the 1920s and 1930s Harlem Renaissance. It is a powerful set of tales contained within the larger narrative of the 369th Infantry Regiment and it helps bolster the heroic qualities of “the Harlem Hellfighters.” The Harlem Hellfighters might be in places “too Hollywood” for the actual historical unit, with occasionally graphic scenes of death and fighting, but for the most part, it is a lovingly-rendered fictionalization of an oft-overshadowed World War I American unit and as such, it is worth reading as a testimony to the lives of those who fought even when others within the country would rather forget that they ever existed. One of the best historically-based graphic novels I have ever read.

No comments:

Post a Comment