The following interview with Caitlin Sweet was done as a collaborative effort between Pat of Pat’s Fantasy Hotlist and Larry (wotmania/OF Blog of the Fallen). We agreed that we would divide the interview into two parts, with Pat concentrating on asking questions relating to the general descriptions of Sweet’s two published books, A Telling of Stars and The Silences of Home and her experiences with the fantasy industry, while Larry would devote the second section toward exploring a more behind-the-scenes look of the author as a person. Here is the result of our collaboration with an author who has much to say and hopefully will be a voice in fantasy for years to come.

The following interview with Caitlin Sweet was done as a collaborative effort between Pat of Pat’s Fantasy Hotlist and Larry (wotmania/OF Blog of the Fallen). We agreed that we would divide the interview into two parts, with Pat concentrating on asking questions relating to the general descriptions of Sweet’s two published books, A Telling of Stars and The Silences of Home and her experiences with the fantasy industry, while Larry would devote the second section toward exploring a more behind-the-scenes look of the author as a person. Here is the result of our collaboration with an author who has much to say and hopefully will be a voice in fantasy for years to come.For the benefit of those of us new to your work, without giving too much away, give us a taste of the story that is A Telling of Stars.

A Telling of Stars is the story of an 18-year-old girl whose family is murdered by a band of Sea Raiders, members of a race cursed by the legendary Queen Galha. The girl, Jaele, sets off in pursuit of one of the Raiders, bent, of course, on exacting a bloody and satisfying revenge. She follows in Queen Galha's footsteps, inspired by her legend, and determined to gather others to her cause. One of these others is Dorin, a young man with whom she conducts a troubled, on again-off again love affair. Dorin changes Jaele, as do all of the people, places and creatures that she encounters; her quest, and her ultimate confrontation with the Sea Raider, end up unfolding very, very differently from what she'd initially hoped for.

The story is fairly simple, since it's told from only one point-of-view, but there are overlapping timelines, and the language is fairly dense and "lyrical" (the adjective most commonly applied to it!). It's also a pretty short book, in fantasy terms: just over 300 pages.

Same as the first question, but in regards to The Silences of Home.

This story is set many hundreds of years before Jaele's time, and follows the seminal events of Queen Galha's reign - the events that became the legend that so inspired Jaele. As it turns out, the truth of the original Sea Raider attack, and Galha's epic revenge, was far, far less flattering than the legend. The story centers around a group of characters whose conflicts and passions mirror and even affect the larger developments within the realm.

Silences is a longer book than Telling; its prose is less poetic, and there are many more points-of-view. The two books may be connected, but they're also very different, which is appropriate and, if I may say so, kind of cool!

What do you feel is your strength as a writer/storyteller?

My inability to make characters and situations black-and-white. See the epic fantasy answer below for more on this!

What author makes you shake your head in admiration? Many fantasy authors don't read much inside the genre. Is it the case with you?

It is actually, and I'm fairly ashamed to admit it! My excuse, these past six years, has been my kids: I now read only before I go to bed, and thus get through only about one book every month or so, if I'm lucky...ah, how times have changed! It took me nearly the entire summer, last year, to read Susanna Clarke's Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, and about that long to conquer Scott Bakker's tomes. Because it takes me so long to read anything, I try to read as widely as I can. So the authors I revere tend to be either genre authors who've been around for a long time (Ursula LeGuin, Patricia McKillip) or non-genre authors whose backlist I've discovered belatedly (Patrick White, an Australian who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in the 1970's, is one of these), or just non-genre authors, like Ian McEwan. All these authors, genre and non-genre, have a fairly stunning command of narrative; they write character-centred stories, using prose that's often unabashedly gorgeous. I also love Latin American authors. Borges is my hero; I was lucky enough to read his Ficciones in the original Spanish while I was at university.

What was the spark that generated the idea which drove you to write both your novels in the first place?

When I started A Telling of Stars (at age 21), I was attempting to recover from serious heartbreak and needed a cathartic creative outlet; I was also trying to write something that wouldn't be like so much of the adult fantasy I'd been reading, which had been disappointing me. (Again, I'll refer you to my epic fantasy answer for more in this vein...) So the spark was both personal and aesthetic. Silences was a more intellectual undertaking: I wanted to explore the relationship between history and legend, truth and propaganda. I was also interested in how individuals interact with the events of history. Thankfully, though, the intellectual spark was accompanied by an equally strong conception of the characters. I find that starting with only themes, and fleshing out characters according to these themes, doesn't work for me.

Given the choice, would you take a New York Times bestseller, or a World Fantasy Award? Why, exactly?

Oh, man, do I have to choose? Can't a girl have it all? ;)

Hmm. I'll go with World Fantasy. Much as I'd revel in the cold, harsh cash afforded by a NYT ranking, I'd revel more in the acclaim of members of the fantasy community I've always admired and enjoyed so much. Seriously!

The fact that you have your own forum on the internet is an indication that interaction with your readers is important to you as an author. How special is it to have the chance to interact directly with your fans?

Incredibly special. I was a bit of a latecomer to the online scene, but thanks to the admonishments of other authors (Bakker foremost among those) and fans, I finally did get my website going, a year ago. My sffworld.com forum followed a little after that. I was utterly blown away by the welcome I found there, and by the generosity of the readers who had no idea who I was, initially, but went off and bought my books anyway. And it's such an amazing thing, to be able to answer questions they have, or respond to comments and criticisms, directly. Like, within minutes! Yes, I'm still a bit wide-eyed - and it's fantastic.

Are you surprised by what little support you receive from the Canadian media? R. Scott Bakker and Steven Erikson rank among the best fantasy authors out there, yet both of them appear to get very little recognition in their own country. Only Guy Gavriel Kay seems to have gone through that obstacle, and that's after years of producing exceptional novels.

The Canadian publishing industry is incredibly small. The Canadian genre publishing industry is microscopic. So no, I'm not that surprised about the lack of media exposure. My first novel was reviewed in the Globe & Mail, which is Canada's national newspaper, but my second wasn't. I got to appear on a few TV shows (Breakfast Television, Richler Ink), do a few readings...I didn't expect much more than this. In Canada, there's a limited amount of review space, and most of it's devoted to international heavy-hitters, or to that odd bird that's known as "CanLit," written by a handful of well-known authors, and whichever up-and-comings manage to fit that mould. Fantasy simply has no "open the paper on Saturday morning to check out the book reviews" kind of presence, here. This is terribly disappointing, but not surprising. Which leads me to your next question:

Honestly, do you believe that the fantasy genre will ever come to be recognized as veritable literature? Truth be told, in my opinion there has never been this many good books/series as we have right now, and yet there is still very little respect (not to say none) associated with the genre.

I'm not holding my breath, sadly. I think that we may see more fantasy authors being accepted in that elusive "crossover" way, which will give them a much broader audience. I'm always interested to see where certain authors' books are shelved, in bookstores: I've found Gaiman, Tolkien and select others on the "Fiction" shelf, far away from that genre section at the back that most buyers of "real" fiction would never deign to set foot in. Putting Gaiman and Tolkien in the Fiction section is a value judgment, and I don't think this is likely to change. You never know, though: perhaps with authors like Gaiman (and Rowling, too) ascendant, in pop culture terms, fantasy will start to get read more, respected more. I've been told many, many times, "I don't usually read fantasy, but I LOVED your books." Which, while it may be a back-handed compliment, is also an indication that people will pick up something they've heard or read about, even if it's not something they'd normally choose. So I guess it's a matter of keeping the online reviews and interviews coming, and the websites up, and the fans clamouring - maybe the rest of the world will catch on!

What made you choose to write an epic fantasy? Were there any perceived conventions you wanted to twist or break? Why do you think that epic fantasy has such a vast and fractured fanbase -- those who either rabidly support or denounce a particular author?

I don't think I've actually written any epic fantasy, yet! I enjoy reading fine epic fantasy, from time to time (and I agree there's lots of it - don't get me wrong), but I don't feel able or even really willing to write it. So far I haven't been interested in working with absolutes, maybe because they too often come off like stereotypes with capital letters. Good and Evil, Magic, Power, True Love, Quest, Battle, Big Finish - I've read and believed in these narrative elements, but I've also, and more often, read and been annoyed by them. I love the escape inherent in fantasy, but I find that the fantasy that usually works best for me involves ambiguity. My own books reflect this, particularly Telling, which was my attempt to turn stereotypes on their head. I wanted to write about a frustrating relationship, a quest that didn't quite work out, a bad guy who maybe wasn't. Silences is similar; the characters are neither fully good nor fully bad, and none of them is evil. This is perhaps (and here's another segue!) why my books often don't appeal to people who adore epic fantasy.

So: why is the fanbase fractured...Because fantasy readers are so accustomed to being defensive about reading genre at all that they naturally get territorial with other fantasy readers, too? Because despite the breadth of interpretation inherent in the term "fantasy," some readers are adamant that one author, or one sub-genre, are the Platonic Forms of authors and sub-genres? I'm not actually sure. All I know is that all the in-fighting belittles the genre. Opinions are fine. Differing tastes: no problem. But it seems so unnecessary, to attack authors or other readers; to savage books that don't conform to one's own tastes, and to savage other readers' preferences. What I do like to see is healthy, constructive, rigorous debate - something that also happens, in fantasy circles. Thank goodness.

What can you tell us about your future projects?

Having just explained why I haven't written epic fantasy yet, I hope someday to try something on a larger scale. Some, dare I say, multi-volume thing. I've been playing with an ancient-Mediterranean-inspired story for half a year now, and although I've just put it aside, I do intend to go back to it. In the meantime, I'll probably stick to the kind of thing I've written so far: character-driven stories, told with a certain degree of lyricism and allusiveness. You never know, though: I might write something totally un-Sweetian... ;)

***

In this second set of questions, the focus is more on the intersections between Caitlin’s personal and professional lives. Instead of focusing so much on the mundane business of how the author goes about constructing the scenes, the emphasis is more on how real life matters, from raising children to related activities to real-life issues that appear to be reflected in Caitlin’s works are addressed. It is important to remember that authors are not composing their works in a vacuum and that their works very often reflect wider issues. So with this in mind, on to the second set of questions and answers done over a series of emails:

Based on many conversations that we've had over the past year, you talk a lot about your young daughters and the activities you do with them. What influence has raising your children had, if any, on how you view life and, by extension, on the writing of a story?

The quick, easy answer is that every single thing I do, think and feel is colored by the existence of my children - but that's way too sweeping! And not entirely true, though that might seem blasphemous to other parents out there. I was a writer long before I was a parent, and writing is still a refuge, of sorts: a place I go, a thing I do, that's about me as an individual. I've never experienced anything as emotionally and mentally consuming as being a parent, and a full-time one at that. (I actually found it much easier to balance things when I was working full-time and being a mother only for the couple of hours before the girls' bedtime.) So I need my writing now, more than ever. It keeps me separate from my mother-self, and usually allows me to return to that other self with a bit more equanimity and patience (though sometimes it doesn't work like that, either: when I was writing Silences, and feeling absolutely euphoric about how it was going, I was generally pretty snappish with my kids).

Practically speaking, having to juggle child-rearing and writing has been a very, very good thing. I'm a mother first, a writer second, but when I do get those two hours to myself in the afternoon, I focus immediately. I was never able to do this, before the kids.

Being a mother has influenced the content of my writing, too: I feel different, describing parent/child relationships, now that I've had children. Alea, in Silences, was a wonderful character to write: I got to trace her development from girl to young woman to pregnant woman to mother of a baby girl, and it felt natural and true. I'm not saying that people who haven't had children can't write about them (that would bring up all sorts of issues of voice appropriation, which I might not be up to tackling!). But now I understand, in a visceral way, how amazing, difficult and mind-boggling having babies and small children is, and that's a definite plus, when it comes to writing about these things.

As for how I view life: it's amazing how children make you remember what it was like to be a child. I watch my girls as they struggle and marvel at life, and find ways of putting these feelings into stories and pictures, and it makes me feel that what I'm doing with my writing is just part of that continuum.

In a recent email, you told me that you were giving a talk to a group of Grade 8 students about 'what it's like to be a writer.' If you don't mind, could you please tell us what you talked about and how the students reacted?

I was told to keep the comments very personal: when I first thought of myself as a writer, how I went about becoming a published one, what it's like to be one full-time. So I did a lot of talking about Caitlin Sweet: The Productive Early Years and Sweet in University: the Long Drought. ;) I brought in some props, including the manuscript of my very first book, written when I was 13. I passed it around; some of the kids flipped through it for a long time. (It's handwritten, as all my first drafts are, and it's WAY neater than all the books that have followed!) I was also asked to give them advice, which, in point form, was:

- be flexible. Write on the subway or in a park, in a restaurant, on little bits of paper - whenever and wherever you feel like it. Don't think you need to have a system, at first. And if strictness ends up being the best, go for it.

- while you're being flexible, be focused, too. Learn how to write, only - to put other things aside, even if it's only for half an hour at a time.

- find a community. This could be friends, family - anyone in your daily life whom you're sure will give you solid, constructive responses to your writing (the ones who'll always love whatever you write are adorable and fabulous, of course, but do try to secure some actual objective readers, too!). Go online and find a weblog or a writers' forum. Find a bunch of sources of feedback: this is the one thing you'll need more than anything. Writing is solitary, and it's easy to lose concentration, confidence and even enjoyment when you spend too much time in your own head.

- expect to have other "real" jobs, while you're writing. Or marry someone rich.

- experiment with all sorts of genres, but be confident about whatever kind of writing you decide you love the most. For years people pressured me to read and write something "real," something that wasn't fantasy. I had no interest in doing this, and I did feel a bit weird about it, initially, a bit ashamed because I was being made to feel like what I was writing was inherently lower-quality than mainstream fiction. After I got over being ashamed, I got mad and defensive, and that was no good, either. Now I'm just proud of what I write. Try for this confidence right from the beginning!

How they reacted...well, pretty much how I expected 45 13-year-olds to react, I guess! The vice-principal, who was in the room for about five minutes, said later, "I couldn't believe how engaged they were with what you were saying!" To which I said, "Aha - so lounging back in your chair, balanced precariously on its back two legs, and smirking at your friends counts as engaged?" To which she said, "Uh huh!" It was a classic pack-mentality scenario: none of them wanted to seem too interested. Once I got one of the students on her own, though (when she was walking me back to the staff room), she asked me all sorts of questions. I do think there were a few in the bunch who really listened. Unfettered by the potential for sniggering or ostracization, the two teachers asked me loads of questions!

One uniformly positive gleaning, for me: when I asked how many of them read fantasy, nearly every single one put up his/her hand. I said, "Not just Harry Potter - other fantasy too" - and the hands stayed up. They were utterly unembarrassed about this particular admission, and this pleased me greatly!

Sounds like a very interested group! I remember from our earlier interview a year ago of you talking about your love for Lloyd Alexander's The Prydain Chronicles and hearing how for many of these students Harry Potter may inhabit a similar place in their hearts. What do you believe it is about The Black Cauldron or Harry Potter that seems to captivate a reader and in some cases inspire them to reach out toward other works? Some people might mean it in a derrogatory fashion, but there does seem to be something 'special' about those books we discover when we are young, those books that are 'the stuff as dreams are made on,' as Shakespeare said in The Tempest. Any thoughts on this matter? Also, how would you relate your published and unpublished writings to the books you read in your childhood?

I wrote A Telling of Stars because I was longing to recapture the sense of wonder I'd always felt as a child, immersed in young adult fantasy - the kind of wonder I wasn't finding in most of the adult genre books I was reading, all those years later. Wonder, escape, emotional and moral resonance: all of these were traits I encountered in the work of Lloyd Alexander, Ursula LeGuin, Susan Cooper, Alan Garner. The stuff of dreams, indeed. I guess it's possible to ascribe dreaminess to the state of childhood itself - except that, when I re-read these books, I feel pretty much the same way I did when I was eleven. So yes, they're special. They enlighten and entertain, at once; they're simple in a gratifyingly elemental way, without being simplistic. (Although I've only read the first of the Harry Potter books thus far, I have the impression that, despite their increasingly voluminous word counts, they're fairly simple narratives too, in that same satisfying fashion. A boy, his friends, his school, a supreme baddie - there you have it!) (I by no means intend to imply that it would be simple to write such books. See below!)

It's strange: although I still think of y/a fantasy as my inspiration, I haven't had the urge to write any myself - or not since I was in high school, anyway. This might be because, at some level, I'm terrified. I remember Lloyd Alexander writing something along the lines of, "It's much harder to write for children than it is to write for adults" - and I believe this, for me, at least. Perhaps this is partly because of the added pressure. Adult readers are often creatures of habit, whose opinions and tastes have largely been formed already; but kids...well, they're more flexible, more open-minded, in terms of what kinds of books they'll tackle. These books have the potential to change their lives. So I've been dancing around the idea of a y/a endeavour - unsure, but also undecided. You just never know...

Since one year has passed since the release of The Silences of Home, what has changed in your professional life?

Actually...not a whole lot! I'm still waiting for my books to be picked up by publishers outside Canada (ah, that elusive U.S. deal), and my sales in Canada continue to be tepid, and there's no mass market release of Silences on the horizon yet. I feel a bit like I'm in a holding pattern, somewhere above my next career development - whatever that will be! But people I trust assure me that it'll just be a matter of time; that I've written a couple of good books that'll gradually start garnering more attention.

In terms of my actual writing process, this past year, things have changed. I'm still only writing in the afternoons for about two hours, as I did when I wrote Silences, but I'm grappling more with concentration and material. (The concentration issue could be due to the fact that I'm such a known quantity at the coffee shop where I write. Anyone remember what happened when Norm used to walk into Cheers?) As I've mentioned elsewhere, writing Silences was a smooth, nearly effortless process. I've felt nothing like that since. I'm not complaining, mind you: I've only written two books, and it's not at all surprising that the writing of subsequent ones will feel different. But it has been hard. I spent about six months planning my next book, then started writing last September - and I stopped writing, about a month ago. Not forever: I'm sure I'll return to the idea (especially since more than 200 pages have been written!). But it wasn't working, for a variety of reasons that were new to me. I'm now back to the planning stage, with a whole new concept. This also feels like a lack of focus, somehow, and it's unsettling. But I'm dealing with it, one anxiety attack at a time! ;)

A positive note to finish this answer on: I'm finally feeling like my books are getting read, by considerably more people than before. This is probably thanks to the Internet, where I took up e-residence about a year ago, on my own website and on sffworld.com. Not only are people reading the books; they're also discussing them, and I'm able to follow it all in ways I couldn't have, a year ago. For example, A Telling of Stars was picked as Book of the Month for May on sffworld, and I know this was because people are more familiar with me, now that I have a forum there. And both books have also been recommended for a wotmania book club. This is good stuff, and I'm grateful for it.

Speaking of this work-in-progress, anything that you can tell us about it? Is it markedly different from the prior story you were writing in terms of plot, style, or feel?

Yes to all of the above! It's funny: just after I'd started writing my ancient-Mediterranean-inspired book, I also started posting about it online, answering readers' queries about it, etc. Then, six months later, the thing stalled. Or I did. Whichever: I'm not writing it any more. So now I'm spooked, maybe - wary of giving away too much, or leading people to expect that I'll be writing something I don't end up writing. Let's just say that my current project is still in the planning stages; that yes, it's very, very different from my prior attempt, as well as my first two published books, and that this is extremely exciting. Ask me this again in a few months; if I'm making amazing headway and am absolutely certain this book will continue to develop, I'll be a bit more generous with the details! ;)

You bring up your experiences with online sites such as sffworld and wotmania. Tell us, what are some of the themes from your books that you've noticed people have talking about that you yourself never really had considered when you were writing the books?

I find it's not so much the themes as the interpretations of them that have sometimes caught me off guard. Telling has been mentioned on several evangelical Christian websites and blogs, by people who claim to have been moved by themes of forgiveness and personal redemption. The themes themselves were ones I was aware of; the interpretation was a surprise. Gender issues also come up a lot. I wasn't attempting to be provocative, when I made Telling's protagonist an 18-year-old girl; I was simply writing what started out as a very personal, quasi-autobiographical story. Then the readers weighed in. "Why a female main character?" asked one male interviewer, with an "aren't I causing trouble?" glance; shortly after this interview, the book was mentioned, in glowing terms, on a website devoted to feminist fantasy. While I don't necessarily mind the plethora of literary criticism-inspired readings of my books, I do want to make it clear that I never explore my themes in any sort of didactic fashion. I had no intention of writing a Feminist Novel - which brings me to your next question.

A recurring topic that I've seen at various sites and blogs deals with gender and fantasy. Over at your official forum, you once addressed that issue in regards to how certain readers were reacting to your books. Would you mind telling us about some of those reactions and to what degree gender plays a role in your fantasies?

My books feature some pretty strong female characters, and some matrilineal societies. They also include a few conflicted, sensitive male characters. This is an organic thing, not a calculated one - as I mentioned above, I had no desire to make gender an overt thematic issue. However, reader reaction to these characters has definitely been overtly gender-based! One reviewer was critical of my male characters because "there wasn't a Conan in the bunch"; another reader called them "ciphers, every last one." The language of the books, and the kinds of stories they tell, have also been both praised and condemned along gender lines. "Quasi-poetic, feminine, self-indulgent" said one of Telling's reviewers; "lyrical and moving and deeply feminine" said another. Which is really, really interesting, to me. Are there masculine and feminine ways of writing fantasy? Do most male authors write fast-paced, workmanlike prose about battles and power politics and kings, while female authors stick to "quieter", more character-driven tales and lusher language? And are there masculine and feminine ways of reading fantasy? These topics feel like quicksand, to me: compelling, impossible to ignore, but also dangerous. I detest generalizations, but I also think it's disingenuous to insist that gender isn't an issue, in fantasy. It is. For a long, long time, genre was written mostly by men, and read mostly by men. That's changed (in fact, some statistics show readership being predominantly female, now), but there's still a certain level of discomfort or even puzzlement when it comes to gender roles. Why else would that interviewer have asked me "why a female protagonist?"

You mentioned the gender thread on my forum. The subject initially took the form of a poll, which asked whether male readers identified more with male characters, and female readers with female characters. The answers seemed to show that male readers generally do have more interest in reading about protagonists of their own gender, while female readers don't really care. Since I myself have no hard-and-fast answer to the gender question, I'll end with a question of my own, posed in that same thread . Something for readers of this interview to ponder!

"Do male/female readers tend to identify with protagonists of their own gender because they might reflect the readers' own experience - or is it because these characters play broader gender roles with which the readers are more comfortable?

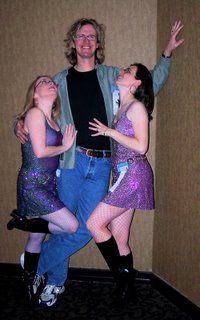

Very good question, very tough to answer, but I’ll provide my personal response as a comment to the post. And now, I had planned asking this ever since we began this interview, but now it might seem to be an odd juxtapositioning of questions, especially after your thoughtful response above, but here's a recent picture that I would like for you to explain. What is going on behind the scenes to make that picture such a sight to behold?

Ah. Yes, well, behind the scenes...

Ad Astra 2006. 25th anniversary year. Many genre luminaries, many scintillating panels and readings and impassioned philosophical discussions at the hotel bar. But THE event of the convention was the Sunburst Award auction. The Sunburst Award (www.sunburstaward.org): a highly coveted Canadian literary genre prize. The auction: an array of genre-related memorabilia. The auctioneers: two oddly attired women with loud voices. Or not so oddly attired, considering it was a con, and the day of the masquerade, at that. Lesley Livingston was in the purple sequins, and I was in the pink (also the name of a classic album by The Band, but I digress). We talked. We strutted. We attempted to channel the many hot alien women of the original Star Trek series (who inevitably ended up tearing Captain Kirk's shirt with their scary 1960s nails). We sold some fantastic merchandise - and then we sold ourselves. Yup. In order to raise funds for a prestigious literary award, Lesley and I offered ourselves as dinner companions to the highest bidder. We stood in front of the crowd, then, and waited, and babbled a bit, into the odd silence that had fallen. Peter Halasz, co-founder of the award, finally made an opening bid. Something pretty modest, if I recall correctly - and I do, because the winning bid was also somewhat modest. But at least there was another bidder. A bidder who was sitting in the back row, but who was about two feet taller than everyone else; a shaggy-haired, legs-in-the-aisle guy whose brain was palpably large. "$35!" this man called - and thus it was that R. Scott Bakker won Lesley and Caitlin at an auction. There were photos, afterward - in the bar, of course. I don't believe he ever did buy us dinner. I expect a refund of $17.50 at some point.

It was fun. I mean, really FUN. And I'm glad there are pictures. At least I think I am... ;)

Fun, yes, I believe ‘fun’ would indeed be the word to describe this! Thanks again for explaining this and thanks again so much for agreeing to do this interview with us, Caitlin. It’s been a pleasure as always and we would like to wish you the best of luck with your career and most importantly, with those near and dear to you.