Saturday, May 31, 2008

Music, world influences, and reading

In a way, such an effort reminds me of reading. A musician who sticks too close to his/her "comfort zone" is bound to become stagnant. Same holds true with writers and their stories. Why wouldn't the same hold try for readers? I know there have been many meme-like posts about "What are you listening to when you read ______?", but I can't help but to think it ought to go a bit deeper than that. Perhaps asking "Is your music full of as many influences and challenges as what you're reading?" might be a better question.

After listening to Plant and Krauss's cover of Townes van Zandt's "Nothin'" over and over again (and watching the YouTube clip below earlier tonight), I found myself wondering not just about Appalachian/Southern influences on writers and musicians alike, but also about the faint North African elements. What authors have listened to music from their native lands and have gone on to create masterpieces that are awaiting adventuresome readers from other lands to discover, to react to, to integrate, and to reinterpret for others in turn to be influenced by them? And while I wonder, waiting for a book by Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz to arrive in the mail next week, here's "Nothin'" for ya:

Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi

Despite having a reputation (especially in Anglo-American circles) for being a very dry, detached, "intellectual" writer who concentrated so much of his writing energy on labyrinths, mirrors, and doubles, Borges was known in his native Argentina for writing a much wider variety of stories. While I'll discuss his early fictions, much of which was influenced by the tone that José Hernández used in his epic poem, Martín Fierro, at a later point, I do want to note that Borges spent over 30 years of his life collaborating with fellow Argentine author Adolfo Bioy Casares on a series of stories. Most of these tales, published under the pseudonyms of H. Bustos Domecq and B. Suártez, were satirical works that parodied the increasingly popular género policial (crime fiction) stories that were becoming the rage in Argentina (as it had in the US and Britain in the late 1930s). Despite the nature of these stories, one can also detect Borges and Bioy Casares' appreciation for the crime fiction genre itself.

Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi (or Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi, as I read this in the original Spanish) deals with six interconnected stories that take the structure of a Holmesian mystery and inverts it to a degree. Instead of a super sleuth who notes precisely physical evidence that others have neglected, Isidro Parodi, or "prisoner in cell block #273," solves all of his clues behind bars. Imprisoned for 21 years for a variety of crimes including embezzlement, Parodi happens to overhear police officials and other socialites discussing a crime that they haven't been able to solve. Wh.ile the obstinate and rather obtuse police officials bear a family resemblance to their peers in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's mysteries, here in these stories, Borges and Bioy Casares turn them into a caustic and often hilarious caricature of Argentinean society of the early 1940s, full of creído and prompousness.

It is for this juxtaposition of an imprisoned criminal sleuth and the foibles of his society that makes Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi a delight to read. Each of the stories builds on the ones that preceded it, until by the final story, there is a tapestry of vividly-drawn characters. Borges and Bioy Casares combine their talents for interesting, ponderous crimes with their wickedly-executed characters to create six stories that work equally well as crime fiction and as satire. Highly recommended for those who are Borges completests, crime fiction lovers, and those who have read and enjoyed Bioy Casares' excellent La invención de Morel

Author Spotlight: Jorge Luis Borges

Time permitting, over the next few months I'm going to write short reviews of several books by Argentine writer, poet, and critic Jorge Luis Borges. Borges is one of my favorite authors and there are so many facets to his writing (and personality) that English-language readers rarely get to see in the relatively few books of his that have been translated so far into English.

While I will eventually cover his more well-known works (Ficciónes, The Aleph, and The Book of Sand, to give them their English titles), I plan on starting with a couple of works that rarely get much mention in discussions of Borges' writings: Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi (a satire of crime fiction) and his poetic oeuvre. From there, it'll be a mixture of his latter writings and his non-fiction criticisms, before I eventually return to re-reading his most famous story collections.

Last year, I wrote a short piece on his last story collection before his death, Shakespeare's Memory, so instead of writing another one on that, consider it the first of many such reviews to come.

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Paul Kincaid, What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction

Imagine that you are holding an unfamiliar book. Curious, you open it up and start reading. Almost immediately you are greeted with strange, sometimes unknown words. "Fuligin" and "grok?" What the hell? Is this something unusual, or are these but clues that what is within is not mimetic?

In the opening section to What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction, Paul Kincaid's latest collection of essays, such scenarios as the above are discussed and analyzed. What is "science fiction?" What does the science fiction reader do when reading tales that contain night unimaginable technologies or creatures? These questions and more he addresses concisely, arguing that far from confusing the reader, such words as the disinterred "fuligin" in Gene Wolfe's series The Book of the New Sun and the neologism "grok," found in Robert Heinlein's A Stranger in a Strange Land, serve to focus the reader's attention even more to what is transpiring in the text, thus making the "weirdness" of the story not something incomprehensible, but rather it permits such stories to be interpreted in a fashion unlike those that would be employed for processing terms and themes for mimetic fiction.

Although the "Theory" opening section sets the stage for this collection of Kincaid's essays on SF that range from the mid-1980s to the present, it itself is rather short, being less than 10% of the book's content. However, the topics covered in this section appear in various guises throughout the remainder of the book. For example, in his "Practice" section, such issues of definition and application are discussed at length in essays such as "How Hard is SF?" and "Mistah Kurtz, He Dead." In the latter essay, Kincaid explores how word usage and symbolism contained in stories such as Heart of Darkness reveal much about the concerns, fears, and sometimes even the hopes of British SF writers vis á vis American SF, for example.

For the most part, Kincaid covers his topics well in his essays. His sections on Christopher Priest and Gene Wolfe in particular will be of great interest for those eager to gain even more insight into their methodologies and approaches to crafting tales. But there are a few weaknesses in this collection, some of which are inherent in the nature of such a collection of essays over the years. In places, Kincaid seems to be repeating himself, although originally the essays were written years apart and often in different publications. In addition, the disparate foci of these essays can create a herky-jerky aspect that is much more noticeable when one reads the collection in rapid-fire order than in pieces over a longer period of time.

But these are minor concerns. A much greater one is that of the latter third of the collection. While Kincaid does an outstanding job dissecting what makes much of British SF tick, his section entitled "...And the World" is rather sparse and lacking in comparison. This was most noticeable in the essay "Entering the Labyrinth," devoted to exploring the themes in Jorge Luis Borges's writing. Kincaid covers the basics well, such as Borges's well-known love for Anglo-American literature and his use of labyrinths. However, there was so much that was barely-discussed or ignored here. For example, the very real influence that his native Argentina had on Borges is given very short shrift. Stories like "The South," (which Borges himself has claimed was one of his best and most representative works) are neglected. While labyrinths and mirrors and the use of golems to represent the intertwining of artifice and reality did constitute much of Borges's interest in Ficciónes, Borges throughout his career did much, much more. He was a poet of some importance in the Spanish-speaking world and while most of his poems were not translated into English until late in his life and afterwards, they contain quite a few themes (loneliness, despair, reflections upon his family past, etc.) that intersect his prose in intriguing fashion.

Other non-British SF authors get even less attention in Kincaid's essays. While Steve Erickson is covered nicely, there is a relative paucity about the American-based New Wave writers such as Ursula Le Guin. The social/anthropological concerns in stories such as hers would have made for an interesting test of Kincaid's "Theory" section's statements regarding how SF readers process SFnal text, but outside of brief mentions here and there, not much is explored. How characters view their (material) cultures and how they interact with it, long a concern of Le Guin (as well as others, such as Doris Lessing in some of her stories), would have made for an interesting parallel with how readers interact with SFnal texts, but unfortunately this is barely addressed.

On the whole, I found What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction to be a thoughtful exploration of a rather difficult subject to cover at length. The fact that the organizational structure (collected essays rather than a single book-length essay) and "blind spots" (much more on how non Anglo-American SF has developed) combine to create a sometimes spotty read is not as much of a condemnation of this otherwise excellent book as this illustrates just how vexing it is to cover a subject that is itself almost impossible to define precisely. Even with its flaws, Kincaid's book serves as a very good exploration of SF hermeneutics. Highly recommended.

Publication Date: March 21, 2008 (UK), tradeback.

Publisher: Beccon Publications

Monday, May 26, 2008

Colonialism, Hegemony, and Fantasy

I finally started reading the graphic novel presentation "update" of sorts to Howard Zinn's 1980 A People's History of the United States, called A People's History of American Empire. I'm about 1/4 in and while I would dispute some of Zinn's interpretations of the Spanish-American War (I think McKinley's reluctance to enter into war was more multifaceted than what Zinn presents in Ch. 2, for example), this is a provocative and nicely-designed popular history of the 110 year-old "American Century."

I am quite sympathetic to Zinn's arguments and have been ever since my undergrad days studying cultural and social histories of Europe and the Atlantic Triangular Trade. Found myself skirting closer and closer to bringing up concerns about hegemony while I was expressing some concern about a perceived "cult of the new" in a forum discussion, before ultimately deciding that it'd be best to discuss such matters here on this blog.

"Hegemony" is such an ugly word. It doesn't contain the harsh hideousness of brute force, as it involves the somewhat active consent and participation of the subordinate with the policies and even Weltanschauungen of the dominant socio-cultural group. It is insidious, following the guns only as a last resort, as it is preferable for its siren-like qualities to be established before the soldiers' footsteps are first heard.

While not often stated directly, worries about hegemony lie behind much of the protests against "globalization" in the ill-named "Third World" or "developing"/"emerging" lands. These protests take many forms. Some have put forth the case that the rise of Islamic jihadism is but the complex interaction between a rapidly-polarizing political elite (often seen as currying favor with the so-called "West"), an impoverished majority denied any real significant share in the new-found wealth, and the pervasive and often threatening "cultural invasion" of ideas and values that run counter to centuries of tradition. Many will argue that it is even more complex than that, but I suspect that perceptions of hegemonic takeover are driving much of the angst in that region (and in many others).

However, this blog is not my preferred place to go into detail about my political beliefs (I think one has sufficient evidence, based on my use of certain words, to have some vague idea at least). But when I was thinking about this, I couldn't help but remember a collection I read last year, edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan, called So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy. In this collection, writers of color address issues of land/scape and self/other perceptions via fantastical or futuristic milieu. One thing that I noticed that I rarely had stopped to consider (after all, hegemony is quite pervasive and persuasive!) is that of "discovery." Why is so little ever really said about the "discovered?" Were these people somehow "lost" before this so-called "discovery?" Is "discovery" a "good" thing? If so, then what is hidden behind the oft-fearful actions in SF stories in which humans are the "discovered" beings (well, in the relatively rare stories where this take places)?

However, this blog is not my preferred place to go into detail about my political beliefs (I think one has sufficient evidence, based on my use of certain words, to have some vague idea at least). But when I was thinking about this, I couldn't help but remember a collection I read last year, edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan, called So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy. In this collection, writers of color address issues of land/scape and self/other perceptions via fantastical or futuristic milieu. One thing that I noticed that I rarely had stopped to consider (after all, hegemony is quite pervasive and persuasive!) is that of "discovery." Why is so little ever really said about the "discovered?" Were these people somehow "lost" before this so-called "discovery?" Is "discovery" a "good" thing? If so, then what is hidden behind the oft-fearful actions in SF stories in which humans are the "discovered" beings (well, in the relatively rare stories where this take places)?I think the reversing or at least consideration of these questions in stories such as those by Hopkinson, Tobias Buckell, and Nisi Shawl (among many others) is part of the reason why I find their stories to be so appealing to me. I hold no truck with "progress" being equated with "goodness" or "advancement." While "development" is a much more neutral term, even there I hesitate to endorse such a viewpoint. Thoughts of hegemonic influence, however, frighten me on occasion. Perhaps it's because of what I've studied in the past or what I'm now witnessing with certain cultural elements from my homeland spreading out, but I just have such an antipathy towards such things. I suspect that this strong disliking might be a strong influence behind the sorts of fictions I most enjoy these days; stories of self-blinded empires teetering on collapse, individuals struggling to forge a new self-identity in opposition to pre-fab cultural norms, societies creating their own "performances" as a counter to the hegemonic influences.

But it's tough finding this in fantasy (or SF for that matter) fiction. One has to dig just a little bit more, since it likely is tougher to market such fiction that runs opposite of "feel good" stories. But I am certain that I have barely begun to scratch the surface. Perhaps others here can suggest some avenues for exploration?

Author Spotlight: D.M. Cornish

Whimsy is a very underrated quantity in storytelling, especially for children's/YA literature. A story can have sparkling prose or a vividly-detailed landscape, but without a hint of whimsy, it can be as dry as dust and as interesting as paint drying. Whimsy, when employed correctly, can give a story that extra Oomph! that attracts the reader's attention, acting as a sort of portal for that reader to enter into a dialogue with the text.

Australian writer D.M. Cornish displays this whimsical quality in spades in his debut novel, 2006's Foundling. Shortlisted for such prestigious honors as the American Library Association's Best Books for Young Adults in 2007, Foundling contained an excellent mixture of deft characterizations (accentuated by Cornish's own drawings, which adds much to the atmosphere pervading the novel), sparkling prose, and above all else, an atmosphere of "Hey! Ya know, this is fascinating!"

I read Foundling back in February (although I had received a review copy back in the Autumn of 2007, I had a huge backlog and didn't try reading it until then). I meant to write a full-scale review then, but I was swamped with job applications and other review commitments and I just kept pushing it off. However, for those wanting a bit more on this debut effort, here is a review I just read which fits well with my own reaction to the novel.

Now Cornish has released the second volume in his Monster Blood Tattoo trilogy, Lamplighter. Clocking in at over 700 pages (and filled with copious appendices and illustrations drawn again by Cornish), it promises to continue the action-packed and intriguing storylines begun in Foundling. I'll be reading Lamplighter sometime in the next few weeks and hopefully I'll have a review written before the end of June. Right now, this little trilogy has the potential to build upon the children's/YA lit renaissance that began 10 years ago with J.K. Rowling and Lemony Snicket's fine serials. I highly recommend that readers who found much to enjoy in those tales to check out D.M. Cornish's work.

Now Cornish has released the second volume in his Monster Blood Tattoo trilogy, Lamplighter. Clocking in at over 700 pages (and filled with copious appendices and illustrations drawn again by Cornish), it promises to continue the action-packed and intriguing storylines begun in Foundling. I'll be reading Lamplighter sometime in the next few weeks and hopefully I'll have a review written before the end of June. Right now, this little trilogy has the potential to build upon the children's/YA lit renaissance that began 10 years ago with J.K. Rowling and Lemony Snicket's fine serials. I highly recommend that readers who found much to enjoy in those tales to check out D.M. Cornish's work.

Sunday, May 25, 2008

Early thoughts on two upcoming releases

This past week, I received two ARCs. The first was from Random House and it was Lord Tophet by Gregory Frost, which concludes the story began in Shadowbridge. The second ARC I received from Tobias Buckell himself and it is the third serial installment in his stories about Pepper and other Ragamuffins, Sly Mongoose. While I will not be writing formal reviews until closer to each book's release date (late July for the Frost and I believe sometime in August for Buckell's), I thought I'd give just a few teaser reactions to each, for those who are curious about each author.

Lord Tophet is a slender book, shorter even than the 270 pages or so Shadowbridge. However, much more is revealed in these pages and Leodora/Jax's stories play a much more prominent role, as there is a dark, destructive force striding the spans. Frost has a nice twist on our own legenda, some of which is referred to directly in places, and the climatic scene was done quite nicely. Lord Tophet almost certainly will get a positive review from me when I sit down to write the full review in 5-6 weeks.

I am about 2/3 into Sly Mongoose right now and am enjoying it quite a bit. Buckell continues to develop his characters and if I'm not mistaken, Sly Mongoose might be his most "political" novel to date, although I use that term in the loosest of senses; it is not didactic or "preachy." As in his earlier novels, Crystal Rain and Ragamuffin, there is an adolescent voice (Timas in this case) who serves as a focal point for the cultural conflicts that often are undercurrents in his novels. I have enjoyed those scenes in which Timas is the focal character and I have high hopes that the novel will conclude nicely, as right now the characterizations are better than in the previous novels and the pacing is smoother. It'll probably be two months before I sit down and write out all of my thoughts.

I am about 2/3 into Sly Mongoose right now and am enjoying it quite a bit. Buckell continues to develop his characters and if I'm not mistaken, Sly Mongoose might be his most "political" novel to date, although I use that term in the loosest of senses; it is not didactic or "preachy." As in his earlier novels, Crystal Rain and Ragamuffin, there is an adolescent voice (Timas in this case) who serves as a focal point for the cultural conflicts that often are undercurrents in his novels. I have enjoyed those scenes in which Timas is the focal character and I have high hopes that the novel will conclude nicely, as right now the characterizations are better than in the previous novels and the pacing is smoother. It'll probably be two months before I sit down and write out all of my thoughts.Hope these teasers will be enough for those who are curious about these two summer releases!

2008 Premio Alfaguara winner: Antonio Orlando Rodrígez's Chiquita

Ever since it was revived in 1998, the Premio Alfaguara has become one of the more visible Spanish-language literary awards. Sponsored by the publisher Alfaguara, who has agreed to publish the winner and to pay $175,000 as prize money, the Premio Alfaguara is chosen by a panel of five judges (rotating, with some of the more famous Spanish-language novelists, such as Carlos Fuentes, serving as judges) from submitted manuscripts that do not contain the author's real name or the true title of the story.

I have read every single one of the revived Premio Alfaguara winners and without exception, I have found each to contain memorable scenes, outstanding prose, deft characterizations, and in a few cases (especially with Xavier Velasco's 2003 novel, Diablo Guardián) traces of the fantastic/supernatural. Yet none of them "feel" like the others. From a half-crazed Cuban ex-soldier who sees a tiger stalking him (Eliseo Alberto's 1998 co-winner, Caracol Beach) to an analogue for the Odyssey (Manuel Vicent's 1999 winner, Son de Mar) to Velasco's demonic guardian angel to last year's winner, Luis Leante's tragic love story set in the Sahara of the last days of Spain's control of the Western Sahara, Mire si yo te querré, each of these stories has its own unique approach towards telling a great story.

The same holds true for this year's winner, Antonio Orlando Rodríguez's Chiquita. Based on an actual person, the diminutive Cuban Espiridiona Cenda, Rodríguez has written a faux biography whose subject, the 26 inch-tall Cenda (known best by her stage name of Chiquita), and her work as a freak show feature attraction in the US during the late 19th and early 20th centuries serve as a fitting contrast for the tumultuous time in both Chiquita's native Cuba and the United States. Through her fake biography, we learn not just about she co-existed with her co-stars, but also about how her Cuban ancestry was played up during the buildup to the Spanish-American War of 1898. We see the Cuba that José Martí immortalized in his poetry and his political tracts written in exile in New York. We get a picture of the US that contains many conflicting and odd angles, from how the denizens of each city on these traveling tours would react to Chiquita and her co-stars, to how the US itself was changing from a rural to an industrial economy during the last years of the 19th century.

Rodríguez is never heavy-handed with these depictions. They exist on the periphery, with the grotesque serving as the focal lens for turning a carnivalesque warped mirror on the crowds gathered together to view the freaks. The prose is direct and to the point, but not at the expense of constructing vivid images of what is transpiring. Chiquita herself feels as though this were indeed her memoirs and not Rodríguez's fictionalization of events from her past. As a historical novel, Chiquita exists on so personal of a level as to make the historical elements just part of the attraction. Yet another deserving winner for the Premio Alfaguara. Highly recommended for those who can read Spanish, as I am uncertain when or even if this will ever be translated into English.

Publication Date: May 9, 2008 (Latin America, Spain, US), tradeback (Spanish).

Publisher: Alfaguara

Assorted Zafón news

Reminds me that I need to get around to buying those YA books of his, since I've seen them in local bookstores. And I guess the wait for the English-language translation will be longer than expected, unless the American release comes before the British one.

Orion has bought four bestselling young-adult novels from Spanish writer Carlos Ruiz Zafón in a "major pre-empt". The books, Prince of the Mists, Midnight Palace, September Light and Marina, have nearly three million copies in print in Spain. The author's adult title The Shadow of the Wind has sold two million copies in English and 10 million worldwide.

UK rights (minus ANZ rights) were bought through the Colchie Agency in New York on behalf of the Antonia Kerrigan Agency in Barcelona.

The Angel's Game, a prequel to Shadow and Zafón's second novel, will be published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in the UK in September 2009.

Saturday, May 24, 2008

Debuts and hype

What is so damn important about discovering THE debut of 2008 or whatever year? Does there have to be such a thing as THE debut of the year for there to be a nice selection of books? Is it more about having bragging rights and pimping this or that author/series/etc. first? I just don't know, as it seems rather pointless to me at times. People being disappointed that there is no "consensus" debut that is a "must-own/read?" What the hell?

If one wants to know the "true" best debut for any given year, wait about 5-10 years at least. Some books are not hyped to the moon immediately, but yet build gradually via word-of-mouth to become bestsellers within a few years. Carlos Ruiz Zafón's The Shadow of the Wind/La sombra del viento took years to rise to megaseller status and that was after Zafón had already written a few other well-regarded releases. Same holds true with a George R.R. Martin, or on a lesser scale, newer authors such as Catherynne M. Valente and Cory Doctorow, to name just two out of many. More often than not, I suspect that the value of a debut relies more on what follows after than upon the initial book. But perhaps others have their own justifications for getting so excited about debuting authors.

Reading the World: Amanda Michalopoulou and Etgar Keret

As I blogged about last week, I am going to be making occasional short reviews of books from the Reading the World consortium of publishers of recently-translated fiction. The first two books I chose were short story collections, I'd Like, by Greek author Amanda Michalopoulou, and The Girl on the Fridge by Israeli writer Etgar Keret. If these two are indicative of the quality of this collection of 25 books, then it bodes well for the other 23, as I enjoyed both of these books for very different reasons.

Michalopoulou's collection of 13 short stories reads more like 13 beginnings and middle portions of an unfinished, untamed draft to a novel. In the eponymous first story, a wife and her husband, a frustrated writer, have a fateful meeting with a distinguished author:

From there, the next story, "A Slight, Controlled Unease," takes up the reins of this story, revealing it to be a story within a story, one that the writer is musing over while another seeks domination. Like matrioshka dolls, each story is nested within each other, creating a vivid, insightful, sometimes ironic or cynical tapestry that sucks the reader into its whirling vortex of character and story. Michalopoulou is a very talented storyteller and her prose cuts through those wasted, idle spaces between words, creating an emotional connection between characters and reader.

"What do you want me to ask? How exactly he beats her? If he pushes her down and kicks her? Is that what you want? To gossip?"

"I want to feel your surprise. You know why your stories have become so hollow? Your characters hear the strangest things in the world and just go on eating their cake. Or smoking."

"Thanks for the constructive criticism! That's just what I need at six in the morning!"

My finger burns inside its splint.

"Why don't we continue this conversation in the morning?" my husband says.

"It is morning."

"All of a sudden I'm exhausted."

"You're always exhausted, every time anything happens to upset the status quo. Just don't take up smoking, please. We've got enough to deal with already, what with the drinking and the constant fault-finding."

He closes the shutters and night falls again, just for the two of us. His exhaustion is contagious. First my brain goes numb, then my hands, then my knees. How will I ever find the strength to take off my clothes and slip into bed? It seems like the most difficult thing in the world. So I just watch him undress.

First his shirt. Then his shoes. He pulls his socks off together with his pants.

A failed writer in boxer shorts.

A failed painter, fully dressed.

We don't hit each other. And we don't embrace.

There are other ways. (pp. 10-11)

Etgar Keret's latest collection, The Girl on the Fridge, reminded me of a harsher, even more cynical and ironic version of David Sedaris. The book description gave some hint of this: "A birthday-party magician whose hat tricks end in horror and gore; a girl parented by a major household appliance; the possessor of the lowest IQ in [the]Mossad..." Keret's stories revel in the cruelties that lie behind the humor, or perhaps in the humor that lies behind the blackest urges in our lives. Told mostly in very brief 1-3 page stories, here is one example, from "Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo":

Etgar Keret's latest collection, The Girl on the Fridge, reminded me of a harsher, even more cynical and ironic version of David Sedaris. The book description gave some hint of this: "A birthday-party magician whose hat tricks end in horror and gore; a girl parented by a major household appliance; the possessor of the lowest IQ in [the]Mossad..." Keret's stories revel in the cruelties that lie behind the humor, or perhaps in the humor that lies behind the blackest urges in our lives. Told mostly in very brief 1-3 page stories, here is one example, from "Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo":

The sub told them to line up in pairs. Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo was the odd man out. "I'll be your partner," the sub said and gave him her hand.

Then they went for a walk in the park, and Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo looked at the boats in the artificial lake, and at a gigantic sculpture of an orange, and then a bird pooped on his hat.

"Shit sticks to shit," Yuval shouted at them from behind, and the other kids laughed.

"Ignore them," the sub said and rinsed his hat off under a faucet. Next came the ice-cream man, and everyone bought ice cream. Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo ate his Popsicle, and when he finished, he pushed the stick between the tiles in the pavement and pretended it was a rocket. The other kids were fooling around on the grass, and only Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo and the sub, who was smoking a cigarette and looking pretty tired, stayed on the pavement.

"Why do all the kids hate me?" Slimy Shlomo Is a Homo asked her.

"How should I know?" The sub shrugged her drooping shoulders. "I'm just a sub." (pp. 99-100)

While this might seem to be of the blackest and perhaps most unfunny of humors, it is an element that underlies the more bizarre tales, such as a mother firing a gun at snot-nosed kids who have begun stoning her soldier son, or that of the least intelligent member of the Israeli secret intelligence force, the Mossad. Often cruel things happen, and yet underneath that is an absurdness that made for some uncomfortable chuckles and laughs. Keret's humor is biting and acerbic, but yet it translates well into English and it makes for some startling considerations long after the last word of a story is read.

Both Michalopoulou and Keret display quite a bit of talent with using the le mot juste to set up their tales and to execute them with élan. Their translators, Karen Emmerich for Michalopoulou and Miriam Shlesinger and Sondra Silverston for Keret, have done outstanding work with making these stories feel as though the reader were experiencing the author's tale first-hand and not via the translation medium. Both of these are highly recommended works and right now they might be the two best short story collections I've read so far this year.

Publication Dates:

I'd Like - April 10, 2008 (US), tradeback.

The Girl on the Fridge - April 15, 2008 (US), tradeback.

Publishers:

I'd Like - Dalkey Archive Press

The Girl on the Fridge - Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Anthology Reviews: Paper Cities

Cities have fascinating and often troubled histories. So much so that the older cities begin to secrete layers of historical clashes and cultural shifts, with elements of the old mutating to fit the needs of the present. Prod a bit under a city's surface and you are bound to turn up a few skeletons and other rotting vestiges of the older cultural orders. Perhaps it might be best to say instead that if one digs deep enough, one will find all sorts of mythical alligators lurking underneath the surface layer.This comment of mine regarding Ekaterina Sedia's The Secret History of Moscow can just as easily be applied to a recent anthology that she edited, Paper Cities: An Anthology of Urban Fantasy. A city is not a monolithic entity; it shifts and warps the viewer's perception from one street corner or block to the next. If New York's Brooklyn and Bronx neighborhoods differ so much that each has its own accent, why can't there be wildly different cities of the fantastic? As Sedia herself notes in the Editor's Note:

I selected these stories because they share the insight into the cities as living entities, benign or sinister, that can shape the existence of their inhabitants. And they share the passion for those agglomerations of flesh and inanimate matter, with all their foibles, glories, and hidden truths.In addition, these stories typically do not represent the facets of the subgenre "urban fantasy;" werevolves and vampires in a modern "real" city do not constitute a major part of what transpires in this anthology of 21 stories. What does happen is that in cities real and imagined, with stories that sometimes stretch for many years or historical periods, people interact with these amorphous entities of brick and mortar, or stone and cement, or perhaps wood and iron and tin, all to create vistas that can be exciting or terrifying.

Forrest Aguirre's "Andretto Walks the King's Way" sets the tone early by describing a rural traveler's travels into the city. With its shifting perspectives and Andretto's perplexity on full display, by the time the story concludes, one begins to get the sense of the mysterious allure that cities can have for those who grow up in the countryside. Hal Duncan's "The Tower of Morning Bones" is set in yet another fold of the Vellum, mixing other mythologies together to create a story that is dense, but ultimately rewarding for those who engage the story.

Other stories that I thought were highlights of this collection were Ben Peek's "The Funeral, Ruined," Michael Jasper's "Painting Haiti," and Catherynne M. Valente's excerpt from her upcoming novel, Palimpsest. In each of these tales, there is a beauty to the prose, one that offsets what is transpiring within the stories, creating a dissonance that enticed me to pay even closer attention to what was occurring. The other stories were only a small step behind these in quality, as I do not recall a story that disappointed me.

Paper Cities is an excellent anthology whose stories ought to appeal to a wide range of readers, especially those curious about "urban fantasy" but who may be uncertain if any of the authors who write in this amorphous field might be worth reading. Like real cities, each city presented has its own facets, its own charms, and its own dangers that the characters come to experience. Highly recommended.

Publication Date: April 1, 2008 (US); tradeback.

Publisher: Senses Five Press

Friday, May 23, 2008

Tripe...and a burning vag

Another insomnia special here, brought to you by coughing and retching, but not the #2:

Reading through some of the links in my Blogroll and I read where Cheryl Morgan has noted yet another in a long series of attention-grabbing inane writings from The Guardian. This time, a novelist named Bidisha takes umbrage about the unkind words some (male) critics have said about J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter and has extrapolated from there in such a fashion as to make a mere tangent seem more deeply-rooted in the matter at hand.

Now for a juicy bit that will explain the title of this post (and why I'm mocking it):

Nice to see such universals being spouted here. Didn't know I was engaging in "man-worshipping," especially since I routinely praise female authors for their stories being excellent stories. Don't think that means I checked in my penis at the door. And speaking of genitalia, the "big burning vagina" bit did cause me to chuckle a bit, since that was more of a movie image and not quite the "cat-like eye" description in the book. But I suppose Bidisha wanted to capture this presumed sense of vaginophobia by using such a vivid (and recent) visual from a movie.A subtle mechanism is operating here, clanking into gear to restore the dominant man-worshipping default mode while reserving a few token high-priestess places for the ladies. In speculative fiction that would be Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood and Ursula K Le Guin, geniuses all. These women are the real deal, rightly worshipped for their vision, philosophical trenchancy and pertinence. But apart from the hallowed three it's men-only when it comes to casual recommendations of mainstream books.

In terms of which books sell plentifully and are acclaimed among knowledgeable fans, speculative fiction is not male-dominated at all - quite the opposite. It is the critical establishment which marginalises women. Bestselling female contenders remain unacknowledged while their male counterparts are robustly namechecked, absorbed reliably into the official history of the genre.

Readers who rave about the scope of Lord of the Rings, in which a club of white men flee (a) a big burning vagina and (b) some black guys in hoods, are simply unaware of the awesome complexity of Katharine Kerr's Deverry sequence of Celtic fantasy novels. They hail William Gibson's prescience, oblivious to Marge Piercy's prophetic sci-fi masterpieces Body of Glass and Woman on the Edge of Time and Liz Williams's intelligent, knotty novels like Darkland.

However, I cannot help but to wonder if she herself might be guilty of not being all that aware of viewer praise. There is only a passing, rather odd mention of Robin Hobb, whose books are often praised to the skies on epic fantasy forums. No mention of books such as Sarah Hall's Clarke Award-nominated The Carhallan Army (Daughters of the North here in the US). Don't know if she's read Nalo Hopkinson's Aurora Prize-winning and Nebula finalist 2007 novel, The New Moon's Arms, which I consider to be one of the best 2007 novels that I've read. Nothing about the recent World Fantasy Award-nominated authors like Susanna Clarke or Catherynne M. Valente, just to name a couple from the past few years alone. None of those except for the Canadian Aurora Awards are "fan" awards; most are chosen from within the writing community or by "the establishment."

But I don't think this is what Bidisha really cared to address. Nuances and subtleties don't make for exciting discussion or controversy. They just make for an increased chance of questioning and exploring, things that run counter to what she is railing against. In a bichrome world, there is no room for such shadings and colorizations. All there is room for, it seems, are big burning vaginas from which pasty white males flee in terror and loathing.

Thursday, May 22, 2008

So there's another round of favorite author polls going around

So, because I'm bored and curious, I'm going to give people who read this blog regularly the chance to speak their peace about this entire thing. If you want to give me a Top 5 list (since that's what the other places are doing) of authors that could be squeezed in under some "subgenre" of "speculative fiction," feel free to do so. If you want to rant and rave about how such things are nigh useless, go ahead. If you really want to be subversive and nominate yaoi fanfic, feel free to do so. I suppose one could treat this as a sort of quasi-recommendation thread as well.

With all that spiel spat out, here are the five authors I've mentioned in those threads that I could justify with a SF label:

1. Jorge Luis Borges

2. Umberto Eco

3. Gene Wolfe

4. Gabriel García Márquez

5. Italo Calvino

What's yours?

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

May 20th Book Porn: The Half-International Edition

These four books (plus two others in a finished state that I've blogged about before) arrived today. Two of them are from outside the Anglophone literary sphere which I purchased, the other two being review copies from DAW Books.

To the top left corner is the 2008 Premio Alfaguara winner, Antonio Orlando Rodríguez's Chiquita, a historical fiction piece dealing with late 19th century/early 20th century freak show attraction Espiridiona Cenda, who stood at only 2'4" in height. Since the Premio Alfaguara winners have yet to disappoint me, I have high hopes for this one. Below it is Etgar Keret's story collection, The Girl on the Fridge, translated from the Hebrew. This is the first book purchased from the Reading the World list I blogged about last week.

In the top-right corner is a reprint anthology, The Reel Stuff, which collects 13 SF stories that were later turned into movies. Needless to say, this book has Dick in it. And finally, an original paperback anthology edited by John Helfers and Martin H. Greenberg, called Future Americas, which I presume is about the US in the future.

Monday, May 19, 2008

A nagging question keeps hounding me

When reviewing a book that depends upon a much more famous work, how much weight ought be placed on the poetic timbre of the original and the more low-key, "earthy' qualities of the latter book? It's an interesting and sometimes frustrating question that keeps popping up as I continue to read bits and pieces of Jo Graham's Black Ships. I love Vergil's Aeneid; I had to translate Book I and parts of Books IV and VI for my intermediate Latin class at UTK 14 years ago. I had a professor that made that poem feel as though it were a paean and not just words written to kiss the boss's ass. To this day, I still on occasion will re-read passages from it in the original Latin because of its inherent beauty.

But Graham's book, like Ursula Le Guin's Lavinia (both of which were released a month or so ago in the US; I shall review both together late next month) depends heavily upon familiarity with Vergil's magnum opus. I'm only about 150 pages into Graham's novel (already read Le Guin's last month) and it's the old issue of prosery or "language" that is troubling me here. I want to finish the book before making any declarative statements, but I suspect part of the issue for me is how does the tenor of Graham's work mesh with that of Vergil's. Don't know if that is a road I want to travel though. Shall be interesting to see what a few weeks off and 250 more pages will do for my interpretation of it.

Sunday, May 18, 2008

Sunday night links

Cheryl Morgan on the Tiptree Award and a review of Riki Wilchins' Queer Theory, Gender Theory: An Instant Primer. I'm always a sucka for identity politics-related writings.

Nic of Eve's Alexandria reviews Michael Chabon's excellent The Yiddish Policemen's Union, which is one of those books I've read but still haven't decided what to say that others haven't already said before.

Fantasy Cafe has a review of J.M. McDermott's Last Dragon, one of my favorite debut novels for 2008.

Seems to be a slow weekend, perhaps there'll be more exciting discussions and/or arguments in the week to come.

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, Steampunk

Personally, I think Victorian fantasies are going to be the next big thing, as long as we can come up with a fitting collective term for Powers, Blaylock and myself. Something based on the appropriate technology of the era; like "steampunks," perhaps ...

- K.W. Jeter, letter to Locus magazine, April 1987

Although Jeter's letter is widely considered to be the terminus a quo for the usage of the term "steampunk" to describe those tales that utilize and (often) subvert Victorian Era steam-based technologies to create fantastical, adventuresome tales, steampunk-like stories can be traced back at least four or five decades, to the inventor/adventurer/conqueror pulp fiction called "Edisonades" and to the reactions to the oft-jingoistic, racist undertones of such novels. It is this juxtaposition of 19th century positivist attitudes towards technology and our more recent concerns with social relations (among a great many other things) that makes steampunk fiction a very popular and creative literary cousin to the cyberpunk movement of the 1980s.

In Ann and Jeff VanderMeer's just-released anthology, Steampunk, the editors begin by noting the influences on steampunk, its various forms and foci, and how interest in all things steam-driven has created a subculture that revels in brass knobs and gears affixed to their computers or other everyday appliances. Since steampunk doesn't have the attribute-defining problems that New Weird fiction does, the editors instead have structured this anthology differently from their February The New Weird anthology. There is an introductory article written by Jess Nevins that explains the 19th century origins of steampunk fiction, which goes into detail describing the rise of the Edisonades and how by the 1960s, authors such as Michael Moorcock had begun writing stories that took the the Edisonades' entrepreneurial spirit and subverted it, creating tales that were much more complex in their focus and which contained quite a bit of ambiguity in regards to the notion of "progress" being sacrosanct. This article sets the stage well for the 13 stories/excerpts that follow and for the two concluding articles written by Rick Klaw and Bill Baker.

The stories chosen represent a cross-section of authors who are primarily known for their steampunk fictions (Joe R. Landsdale, James Blaylock, and to a lesser extent, Paul di Filippo) as well as those whose works utilize steampunk tropes on occasion (Michael Chabon, Ted Chiang, Michael Moorcock, and Jay Lake, among others). Although some of the more famous steampunk writings do not appear here because they are novels (such as William Gibson and Bruce Sterling's The Difference Engine), the stories that do appear in this anthology are very strong choices.

I usually don't spend much time reviewing individual stories when I comment on anthologies, since I am much more interested in seeing how "well-glued" the anthology is rather than elaborating at length on each of the stories. However, I do want to point out that in each of the stories presented here, we see evidence of the various motifs that Nevins discusses in his introductory article. We see the use of an industrial golem in Ted Chiang's brilliant "72 letters." In an excerpt from his 1971 novel The Warlord of the Air, Michael Moorcock explores questions of whether or not gadgetry employed for destructive purposes is something that ought to be glorified. Some of the tales are funny or satirical, such as Paul di Filippo's "Victoria," while others contain gruesome warnings, such as that embedded in Jay Lake's "The God-Clown is Near."

As I read each of these tales, I could not help but to reflect back to not just Nevins' introduction, but also to the closing pieces by Klaw and Baker. In their pieces, the two discuss what it is about steampunk that creates such a lasting impression on the reader or upon the movie/TV viewer who enjoyed shows as diverse as the old Jules Verne-based movies from the 1960s to the original TV version of The Wild Wild West. As I read these stories in light of the point raised by these articles, I could not help but to remember reading one of the last major Edisonades, the reworked and updated Tom Swift novels released in the 1980s, and thinking about how there was so much that appealed to me then but which now leaves me feeling uncomfortable with the underlying assumptions behind writing such tales. Reading these steampunk stories served to highlight their distinctions from the earlier Edisonade form, while they still managed to capture some of the energy and spirit that makes such works exciting reads. Based on this, the VanderMeers' latest anthology works both as a historical piece that concisely tells the origins and importance of the steampunk subgenre and as an enjoyable set of tales that ought to appeal to a wide range of readers. Highly Recommended.

Publication Date: May 1, 2008 (US); tradeback.

Publisher: Tachyon

Possible new Gabriel García Márquez novel by year's end?

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Reading the World

In June, Words Without Borders will be launching its series of related reading guides to help readers from the US and across the globe to start reading clubs based on these works. And while this blog traditionally has concentrated on speculative fiction, I myself read extensively outside of genre and therefore, time and money depending, I plan on reading 1-2 of these books in the coming months and reviewing them here. Hopefully, there'll be much of interest to all sorts of literature fans and perhaps some questions can be asked and discussions generated here and elsewhere regarding these books and others.

Tons of new books and magazines plus upcoming reviews

In this photo, there are the Nov/Dec 2007, Jan/Feb 2008, and March/April 2008 issues of Weird Tales, the Stevenson book I mentioned above, the ARC edition of Barth Anderson's second novel, The Magician and the Fool, Paul Kincaid's What It is We do when We Read Science Fiction, and Farah Mendlesohn's Rhetorics of History.

In this photo, there are the Nov/Dec 2007, Jan/Feb 2008, and March/April 2008 issues of Weird Tales, the Stevenson book I mentioned above, the ARC edition of Barth Anderson's second novel, The Magician and the Fool, Paul Kincaid's What It is We do when We Read Science Fiction, and Farah Mendlesohn's Rhetorics of History. In this second photo, there is the hardcover edition of Alan Campbell's second novel, Iron Angel, the ARC for Gene Wolfe's An Evil Guest, James Braziel's Birmingham, 35 Miles, and the ARC edition of Kay Kenyon's recently-released A World Too Near.

In this second photo, there is the hardcover edition of Alan Campbell's second novel, Iron Angel, the ARC for Gene Wolfe's An Evil Guest, James Braziel's Birmingham, 35 Miles, and the ARC edition of Kay Kenyon's recently-released A World Too Near. And this final set includes photos of the ARC edition of Howard Zinn's graphic novel/non-fiction, A People's History of American Empire and the ARC for D.M. Cornish's second novel, Lamplighter.

And this final set includes photos of the ARC edition of Howard Zinn's graphic novel/non-fiction, A People's History of American Empire and the ARC for D.M. Cornish's second novel, Lamplighter.It was fortuitous timing on receiving the Weird Tales magazines, as I am planning on subscribing to it in the next month or so when I finish paying off a few more bills. I will read and review these issues sometime before the end of the month, time permitting.

Also, here is a tentative listing of reviews that I plan on doing before May is complete. Subject to change, of course, this list will be full of anthology reviews:

This weekend: Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (eds.), Steampunk (anthology); Ekaterina Sedia (ed.), Paper Cities (anthology)

May 19-25: Ellen Datlow (ed.), The Del Rey Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy (anthology); James and Kathyrn Morrow (eds.), The SFWA European Hall of Fame (anthology); Steven Hall, The Raw Shark Texts; Sarah Hall, Daughters of the North

By May 31: Cory Doctorow, Little Brother; Isamu Fukui, Truancy (these two as a dual review); Jeffrey Ford, The Shadow Year; Paul Kincaid, What It is We do when We Read Science Fiction; Farah Mendlesohn, Rhetorics of Fantasy (again, these perhaps will be a dual review)

Some of these of course might be bumped back into June and others might be added to this list. Hopefully by writing this tentative review plan here, I can force myself to stop being lazy, as with the exception of the last two books mentioned, I've read at least 1/2 of all the ones mentioned here.

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Luís Vaz de Camões

Mudam-se os tempos, mudam-se as vontades

Mudam-se os tempos, mudam-se as vontades,

Muda-se o ser, muda-se a confiança;

Todo o mundo é composto de mudança,

Tomando sempre novas qualidades.

Continuamente vemos novidades,

Diferentes em tudo da esperança;

Do mal ficam as mágoas na lembrança,

E do bem, se algum houve, as saudades.

O tempo cobre o chão de verde manto,

Que já coberto foi de neve fria,

E em mim converte em choro o doce canto.

E, afora este mudar-se cada dia,

Outra mudança faz de mor espanto:

Que não se muda já como soía.

(Time changes, and our desires change. What we

believe - even what we are - is ever-

changing. The world is change, which forever

takes on new qualities. And constantly,

we see the new and the novel overturning

the past, unexpectedly, while we retain

from evil, nothing but its terrible pain,

from good (if there's been any), only the yearning.

Time covers the ground with her cloak of grren

where, once, there was freezing snow - and rearranges

my sweetest songs to sad laments. Yet even more

astonishing is yet another unseen

change within all these endless changes:

that for me, nothing ever changes anymore.)

A week or so ago, I was browsing through Amazon and wanting a poetry fix (still do, actually), decided to purchase two books by 16th century Portuguese writer/poet, Luís Vaz de Camões. The first was an epic poem freshly translated into English, The Lusíads, the second being a bilingual Portuguese-English collection of some of Camões' poetry. The quotation above is from that second book, Luís de Camões: Selected Sonnets. I just found "Os Tempos," or "Time," to be an interesting sonnet and thought I'd share it here, since I'm going to be busy for part of the weekend.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

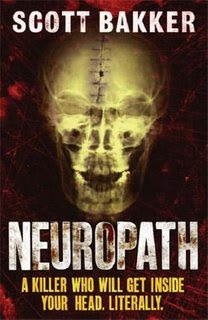

Thoughts regarding Scott Bakker's Neuropath

This shall not be a typical review for me. Unlike virtually all others who have received review copies over the past few months, I have known at least some of the details of this story for almost four years now and instead of focusing directly on the story itself, I would rather concentrate on its genesis and some of its possible implications.

When I met Bakker at a Nashville booksigning in June 2004, he said to a small audience that consisted of some of his old grad school buddies from Vanderbilt and a couple of others (including myself) that he had recently begun writing a near-future thriller based on a dare from his then-fiancée Sharron, who preferred that genre over the epic fantasies that he enjoys reading/writing. But early on, from what I recall from a few email conversations and interviews that he did with me and with others, he decided to mix in elements of his Ph.D. dissertation and craft a tale that would be provocative, unsettling, and if the reader were willing to commit to the Argument that he presents in the book, something that might be harrowing for a year. Needless to say, all of this interested me, especially in regards to questions revolving around choice, free will, and the possible illusory natures of both. While we disagreed then (and now) on some of the particulars (I am much more optimistic about matters regarding both), Bakker's questions sparked quite a few thoughts that occupied my waking and sometimes sleeping hours.

Fast-forward to February 2006. Bakker had just completed a complete revision of this thriller, called Neuropath, and he asked me and Jay Tomio if we would like to read the draft while he and his agent would attempt to sell this story. He warned us beforehand that it was a "difficult" story and one that likely would not be appealing to the majority out there due to its visceral qualities and its disturbing questions. Undaunted, I agreed to read the draft.

The draft was everything he said and more. It is a very bleak novel, with its few lighter moments serving only to set up even more devastating revelations. And unlike most thrillers, there was no catharsis at the end. Instead, the ending is so chilling, so personal in a sense that I was sucked into imagining myself in the place of the protagonist, Thomas Bible. There was no redemption, no "saving moment." Instead, it closes with a realization that the traumas endured, the horrors realized, all of those were but the stripping away of protective layers; I felt exposed afterwards. Made for quite a downer for a couple of days, as even my dreams dealt with the implications of what was shown in that novel. Totally unlike 99% of the other novels that I've read over the course of almost 30 years of reading.

Bakker was correct in noting that this would be a tough sell, as it took well over a year to find publishers that would release the book. Talking about matters involving the manipulation of the mind (and therefore the body) does not make for a pleasant read, regardless of how well-written and plotted the novel might be. Considering that Neuropath utilizes some of the tropes of the thriller genre, perhaps it might be best to discuss how well it succeeds on that level.

The few thrillers that I've read tend to be short, sharp staccato bursts of dialogue and action that moves at a fast clip to a (somewhat) telegraphed conclusion. Neuropath on the other hand, while it nails the tense, frightening scenes that drive the early portion of the novel, might be odd and disjointed to thriller fans because there is so much exposition. Those who don't want to think while they're reading a plot-heavy novel probably will find Thomas Bible's reminisces about his friend-turned-FBI suspect Neil Cassidy to be rather long and distracting from the plot. For the first 200 pages of this 300 page novel, Bible's thoughts, his self-denials, his worries, his fears dominate the book, creating a sensation of a sputtering start perhaps for those who desire a head-on adrenaline rush.

However, the final third of the novel is packed full of surprising revelations, horrifying actions, and a twist ending that does serve to provide a definitive end to the action, if not to the implications that led up to that action. It is a suitable conclusion, but not necessarily the one that most readers would want, but it does flow quite nicely with the "Argument" between Bible and Cassidy that is threaded throughout the novel.

It is strange novel to review. It meets its purposes and is written well. It creates an emotional connection with the reader, but through appealing to the fallacy of reason than by any real attachment to the characters. There is nothing cathartic about its conclusion to offset its disturbing implications. It is not a story that will make someone feel better for having read it. But it is a tale that does make a strong connection and as such, if one engages in the "Argument," it might be a moving book, but if one fails to engage in that "Argument," the book and its premise will be utterly unappealing. Therefore, I can only recommend Neuropath, despite its merits and despite my personal appreciation of what Bakker has accomplished here, to those who are willing to engage their minds with what is transpiring in the text.

Publication Date: May 2008 (UK); June 2008 (Canada); unknown US release date

Publishers: Orion (UK); Penguin Canada (Canada)

Monday, May 12, 2008

Amusing fandom differences

One thing that I've noticed that stands out are reader reactions to books and authors. Those who visit my blog due to links from other blogs, based on the conversations that I've had in Comments section here, seem to prefer standalone, smaller volumes for their books. Many of the books that I've investigated as a result seem to bear this out. But on the forums, in particular Westeros, wotmania, SFF World, and to a lesser degree Fantasy Bookspot, the "average reader" seems to be wanting more and more multi-volume epic fantasy doorstoppers.

For example, in this thread over at Westeros, a reader says this in regards to Steven Erikson's Malazan Book of the Fallen series:

Even the editing is subjective and a matter of taste. I can't comment as I just read Erikson's first and part of the second, but the biggest flaw of the first book is that it is too short.Interesting, since I'm of the opinion that such books, interesting as they are in pieces, tend to be too long, without a tightly-written narrative. Too much exposition, although short epics tend to be viewed as an oxymoron, I know.

Related to this are the various "recommendation" threads that you'll see at these places. Almost without exception, this are "more of the same" recommendations and not recommendations for people to shift gears and to try something completely different. There is almost a meme-like quality to requests for new books now. For example, someone says, "Well, I've finished Martin's last book, what are other books that I ought to try?" Almost invariably, you'll see these names mentioned: R. Scott Bakker (and as much as Scott and I are good friends, this isn't about the personal merits of any of these books here), Steven Erikson, and more recently Scott Lynch, Joe Abercrombie, and sometimes Patrick Rothfuss or Brian Ruckley.

Is there much in the way of differences between them? To some degree, yes, but ultimately each is a multi-volume effort, spanning 3 to 10 volumes (planned) in length, each set in a cod-medieval setting. I like epic fantasies on occasion and I do agree that most of these authors have their merits (despite whatever mischief I might start up with Abercrombie on occasion), but if (wo)man shall not live by bread alone, neither should the reader live by just one style alone. Brain rot and all that nasty gunkiness, you know.

Seriously though, there is a sense of insularity that takes place on a great many of these forums. "Literary" or "Mainstream" fiction generally is either verboten or is looked at strangely; it is a weird beast to them. A couple of days ago, one of the moderators at Westeros compiled the results of a month-long reader "poll" as to which were the readers' five favorite SF/F writers. The results are hardly surprising for the first 10-15. It is around #15 that one begins to see which forum regulars read outside just one particular genre box (and yes, I was quite pleased to see that Jorge Luis Borges received a single vote more than Robert Jordan. I am that petty). But on the whole, the vast majority of books mentioned were for multi-volume secondary-world/epic fantasies.

The inverse seems to be true for blogs that are not strictly tied to the blogger's interactions with a particular set of forums. If I go read the comments on say Fantasy Magazine, the concerns, discussions, and whatnot often differ substantially from what transpires on a forum. I'm more likely to see a post on I Distrust Female Authors on a forum than I am to see a discussion of gender roles/expectations in a reflective, considered fashion. Blogs are different beasts from forums and since by their very nature are person-centric rather than community-centric, there tends to be a greater sense of variety. But yet it is interesting how few blogs I visit where one is likely to say, "Ya know, Steve Erickson and Steven Erikson both have their strong suits and I'd highly recommend both for the reader to consider." More often or not, LJs, blogs not kept by forum regulars, and author blogs tend to remain outside the Pale as far as forum regulars are and for the most part, the inverse applies as well.

I have no axes to grind here; if anything, I mostly understand that people have different tastes and they gravitate towards those tastes. I just cannot help but to wonder if in a hypothetical conversation between a die-hard epic fantasy-loving forum regular and a "literary fantasy"-preferring blogger there might be "translation" difficulties. If I struggle at times to explain why I believe epic fantasy characterization can be improved and strengthened by streamlining over increased exposition, perhaps it might stand that it's a more general difference in world-views on such matters.

But what do I know? Both Erickson and Erikson in my opinion deserve some consideration, but who reading this has ever read anything by either/both of them? Or for that matter, who wants to consider/debate Jennifer Stevenson's alteration of Arthur C. Clarke's maxim: "Any magic with sufficient internal consistency is indistinguishable from technology." I read that one today and she hit something that I've been wondering about all along when it comes to plot/setting - why explain every damn thing to the most minute of details?

Just something else for my achy self to consider as I get ready for bed in a few minutes.

Sicktime Discoveries

Of course, there are some benefits to being ill. One, if the vocal cords are affected, I can do a fairly mean Godfather impersonation with my raspy voice now. Another is that I can just lie down in bed and not feel that guilty about lying down and not doing anything; nobody wants you around when you're sick, you know.

But a third thing that comes from being sick happened this morning. While I normally take my almost-noon lunch break here at my house (since work is a 5-10 minute drive and I hate being closed in my claustrophobic education office cubicle), I managed to have time to see what was in my mailbox. Sometimes, when you're feeling icky and you know your breath reeks even more foul than that of Shakespeare's erstwhile mistress, little things amuse you even more. Take for example what I discovered in my mail:

I suppose by now some would have squeed! in delight at receiving an autographed book that one ordered from the editors of the just-released Steampunk anthology, Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, but sick people don't squee! If anything, they just gurgle, hack, cough, grin, smile, and carry the treasure to their bookshelves. At least this is what this sickly person chose to do in lieu of squeeage!

Now of course there were other books. These books doubtless would appeal to quite a few and since one of them forms part of my next paid reviewing arrangement, it might be best to show these off before the hacking, wheezing, and sniffing begins anew:

Sadly, the camera phone was being balky at this time, so besides the aforementioned book, here are its three delivery companions: The Queen's Bastard by C.E. Murphy; Black Ships by Jo Graham (this and Ursula Le Guin's Lavinia will be reviewed together as a piece for Strange Horizons, perhaps for a late June/early July issue); and The Brass Bed by Jennifer Stevenson (who wrote the delightful trash sex magic a few years ago).

But as much as I'd love to be torn by which to read first, the worst part of being ill, the lack of energy, is upon me. So it might be a day or two before I get to these. But they certainly were a nice cheer-me-up on a sniffly day like today.

Sunday, May 11, 2008

My Amazon review of Carlos Ruiz Zafón's El Juego del Ángel

Translation of the El País Interview with Carlos Ruiz Zafón

"I am the biggest of the dragons."

El País interview with Carlos Ruiz Zafón

Conducted by: Karmentxu Marín on 4/20/2008

Translated from the Spanish by Larry Nolen and Oscar Sanabria

He is 44 years old and to the question of what would he want to have that he doesn’t already have, he answers, "more time." He speaks softly - as a matter of fact, he ironically announces himself with "the mute is now here." - and he says that narrative languages, music, architecture, cinema, comics, and history interest him. He plays the piano, synthesizers, computers, and "all that one can plug in and make noise. They are," he adds, "my favorite toys."

Question: El Juego del Ángel is, again, a book inside of a book?

Answer: No. In The Shadow of the Wind I had that game. This is a game of angels, of shadows, and of mysteries.

Q: You have said that you cure awards with two aspirins. Has Bayer given you an apartment?

A: The awards, no, the too elogistic critics. Two aspirins and a nap. Bayer hasn’t given me an apartment, but now that you mention it, it wouldn’t be a bad idea. I am a great consumer of aspirin. You have given me an idea.

Q: Are you a talented person?

A: I don’t know. I intend to be.

Q: Are you above good or evil or is it just my view of it?

A: No, I’m not above or below. I am more or less in the middle, with all the world.

Q: Well, you give the impression of someone who doesn’t really lose any sleep over critics.

A: No, no I don’t. I am not obsessed by a review or what someone says on a blog.

Q: Do you see yourself more as an enfant terrible or more like Daniel the Mischievous?

A: I am a little old to be an enfant terrible. Neither one nor the other. There are those who see me as being very mischievous in many things. But I intend to appear to be a little saint.

Q: Did you send a ham to Joschka Fischer for the free publicity that he gave for The Shadow of the Wind?

A: No, no I didn’t send him a ham. If I had to send him a ham for every book that he praises...Although he has the gentility to send me one of his books each time he publishes one.

Q: How many aspirin did it take to digest the 10 million books in 30 languages and 50 countries?

A: None. It’d have been many if the book hadn’t interested anyone. The aspirin aren’t for the successes, but instead for the elogistic critics or the high-sounding commentaries.

Q: Are Aznar’s Letters to a Spanish Youth or The Memoirs of César Antonio Molina in your Cemetery of Forgotten Books?

A: It would be best to deny them entry. Both of them.

Q: "The kiss one cannot nor ought to explain a priori." Do you kiss suddenly?

A: No. I give advice.

Q: And the Spanish woman when she kisses?

A: Kisses in truth? Depends upon the Spanish woman and the frivolity, which has different grades to it.

Q: Are you in favor of impossible loves?

A: Not especially. Normally, impossible loves are not loves. There is a technical word, I don’t know if it’s infatuation, which sounds very pedantic.

Q: You, for infatuation, don’t need two aspirins. You don’t suffer from it.

A: No. I have suffered in my boyish years, like all the world.

Q: When The New York Times compared you to a cocktail between Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges, and Umberto Eco, did you roll your eyes at that?

A: One of the few advantages that writers have is that they don’t have to opine on the opinions of those that are poured over them.

Q: Do you lack passion?

A: No. I have the same passions, the same phobias, and the same manias as any other person.

Q: And what about the temptations?

A: I believe that I have them well hidden.

Q: In what area do they move?

A: I wouldn’t know to say to you. When there they are, normally I succumb to them, and they stop being temptations.

Q: "Writers are not so famous as the football players, the politicians, or serial killers." Do you yearn for some of those?

A: No (laughs). I am very content to be what I am, and to be much less famous. For the football players I don’t have the conditioning or age. And for the politicians, age, maybe so; but the will, no.

Q: And the serial killer, nothing to add...

A: Nope. At the moment I don’t have the sense of being tempted to kill anyone. But if I feel it, you’ll be the first to know.

Q: Did you settle in Los Angeles in hopes of getting a part in Hollywood?

A: Well, no. It was because I felt like it. And I never intended to be an actor.

Q: Do you have a soul?

A: I don’t know. I have a conscience.

Q: You with the dragons, Vargas Llosa with the hippopotamus...other perversions?

A: It is very innocent. The collection of dragons, poor little ones, they do nothing, and I less. If I have a love it is music. It is my main drug.

Q: Are you the biggest of your monsters?

A: I am the biggest of the dragons, perhaps. That’s why I collect the others.

Q: What St. George has the capacity of killing you?

A: Interesting question. I am sure that I don’t lack St. Georges who would want to make me disappear off of the map. Doing it is an entirely different matter.

Q: You assure that you almost never say what you think. How many lies have you told me?

A: All that I was able to tell. It is my obligation, in an interview like this one.